“When things get so big, I don't trust them at all

You want some control, you've got to keep it small

Hey!

D.I.Y.”

— Peter Gabriel, “D.I.Y.”

Do It Yourself. It’s been a theme in my life lately. I’ve never claimed to be a particularly handy person by instinct or training. Nor am I overly motivated by frugality. But what I’ve discovered is, fixing, making, or simply doing something moderately challenging—whether that is baking a cake, replacing a driveshaft, or changing a light fixture—pays back in dividends of satisfaction and confidence beyond what money can buy. Over the decades living in my house I’ve gotten increasingly more ambitious with projects. I installed new toilets and a sink, plumbed a gas range, figured out how to swap the flame sensor in my boiler, and have built a few crude garden tables out of old pallets. In the past few weeks, I helped my girlfriend build a new gate and drywall some new construction. None of this is particularly impressive. Plenty of people can do all of that, and YouTube has made learning new skills way more accessible. DIY is a circular phenomenon. The more you do, the more you want to do, and confidence and satisfaction grow.

So what does this have to do with a Land Rover? There’s an aphorism that goes, “Land Rover: turning owners into mechanics since 1948.” (There’s another, less relevant one: “75% of all Land Rovers ever built are still on the road. The other 25% made it home.”) It is largely true, but really only applies to the older Landies. Open the bonnet of a new Defender and I suspect there’s a warning sticker that says you require a PhD. in computer science to do any work on it. Since owning not one, but two, old ones, I can attest to the fact that not only are regular repairs and maintenance necessary, they’re also encouraged. The vehicles are simple to figure out, and fairly simple to fix, other than corroded fasteners and the availability of spare parts. I’ve replaced a starter motor, wiper motor, a propshaft, a carburetor, rewired lights, swapped the horn, changed out the whole dashboard, done countless fluid changes, and plenty of other odd jobs. While some people might wonder why anyone would sign up for that level of involvement, I relish it. And it also points to a bigger issue.

With so much of our modern lives, there is little need to know how anything works. On the one hand, many products are more reliable, meaning less repairs are needed. But things are also more disposable these days. Few people stitch up ripped clothing, or take apart a fan to see why it stopped oscillating, because things are often not designed to be disassembled or repaired, and are easily replaced. Even cars tend to be leased and returned every few years, and serviced at a dealership. But hanging sheetrock helps you learn what’s behind your walls and how to cut angles. Changing a broken clutch cable (my old VW Rabbit) taught me what was going on every time I shifted gears. I believe the Land Rovers I own are some of the last machines truly designed to be easy to work on. Everything is mechanical, with levers and springs and rotating shafts, and big bolts, and minimal plastic. They not only encourage one to do your own work on them, they encourage you to use them for work, and play.

While many car ads tout a vehicle as utilitarian or adventuresome, the fact is, if you own a new SUV, you’re probably less keen to park it outside year round, leave doors unlocked, shovel dirt in the back, or strap something to the roof, much less climb up there. Just in the past few months, I’ve loaded down the rear bed in the Defender with 800 pounds of firewood, hauled a full-sized door and many 10-foot lengths of lumber, strapped sheets of drywall and a giant pallet to the roof. And that’s just the work side of things. My girlfriend and I also took it camping a couple weeks ago, sleeping cozy on a mattress pad in the back. We mounted a collapsible awning to the roof rack, deployed a roll-up welcome mat on the ground outside the back door and it was home, sweet home. A specially designed grill, or braai, was transported on top of the bonnet-mounted spare wheel, and we used it to cook our dinners—chicken skewers one night and a Greek style feast the other. The last day, after the campfire smoldered to death, we took down the awning, stashed everything in back, and off we went, trundling home.

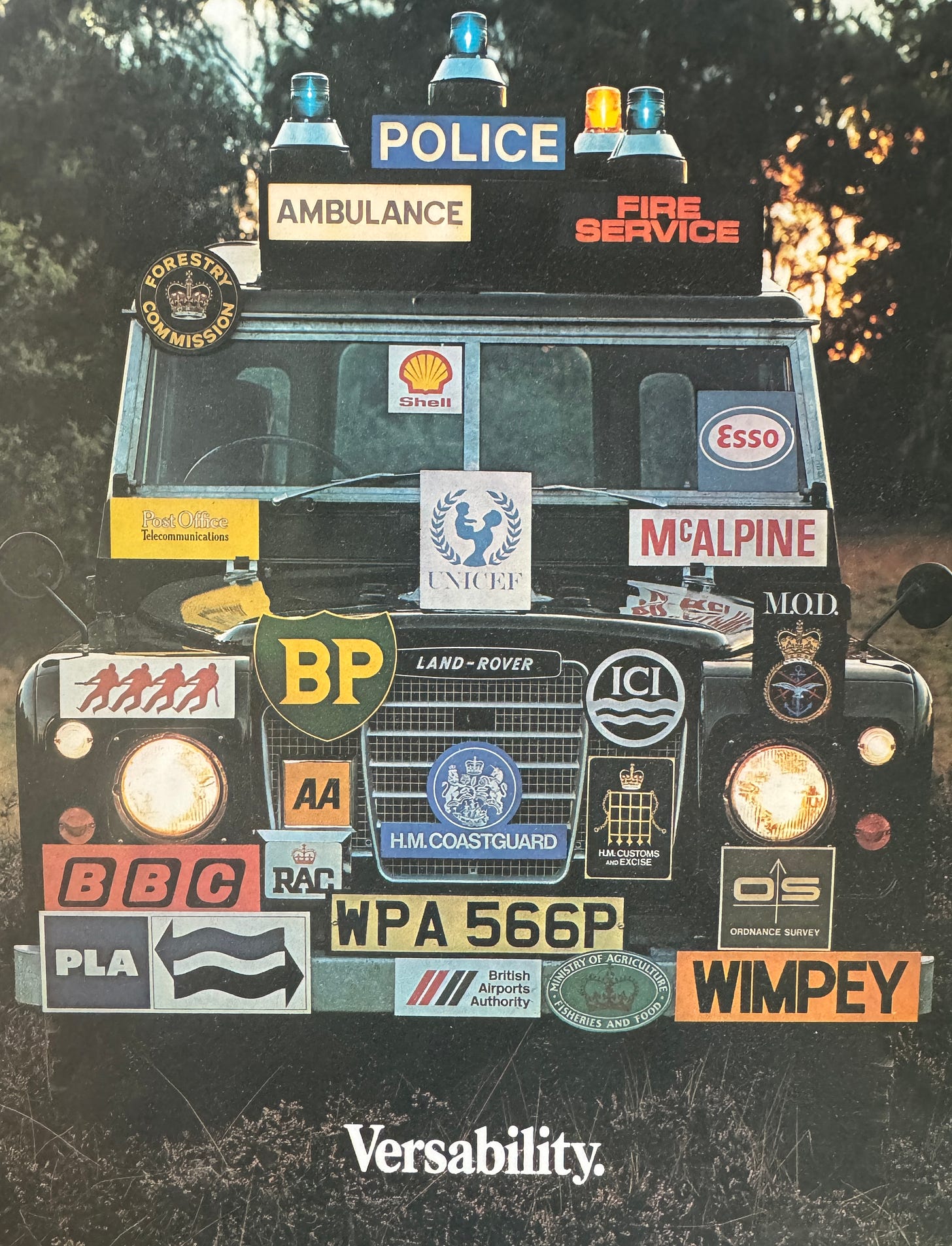

There’s an old magazine ad for Land Rover that shows the front end of a Series III covered in various decals from different disciplines and organizations that used the vehicles. The tagline was a single, made-up word: “versability,” and it remains apt for the way I’ve used my Land Rovers. They’re versatile, able, and fun. I’m not afraid to stand on the bonnet, climb up on the roof, get it dirty or scratched, or load it with all manner of building or garden supplies or camping gear. The Defender has been off-road, waded through a flooded stream, and started on the coldest winter mornings. The Series III towed a police car out of a snowbank, has been filled with mulch, and both vehicles function as dog taxis on a regular basis. I wrote once before about becoming a “truck guy.” The fact is, I don’t love trucks for the reason a lot of people do—the high seating position, the power to tow stuff, the road presence, or the prestige of ownership. Nor am I someone who “needs” a truck for my job. The fact is, for much of my adult life, I preferred, and owned, a number of decidedly more sporty vehicles—an Alfa Romeo Spider, an Audi TT, and a BMW hatchback. So to be almost a decade into owning two very agricultural old rough and tumble trucks might seem surprising. Maybe it’s my time of life, but Land Rovers—old ones—seem to fit where I’m at now. More willing to accept imperfections, a slower pace, and an emphasis on getting my hands dirty.

With two vehicles that beg to work, as well as to be regularly maintained and fixed, I’ve become emboldened to simply do more myself in other aspects of my life. Hauling firewood home to split, drywall to be hung, pallets to be broken down and repurposed, all the while having to fix the truck itself, has become a seamless representation of my current ethic. But, as we know, “all work and no play make Jack a dull boy,” and again, the Land Rovers deliver. Stripping the roof off the Series III and taking the dog for a joy ride, or loading up the Defender with camping gear for a weekend away also slot seamlessly into the overall picture I’ve created, one of adventure, hard work, and a measure of self sufficiency.

Could a different vehicle work as well? Possibly. A Prius will carry a 10-foot piece of lumber and people have been known to camp in a Honda Fit. But would you caulk the roof seams or re-wire the wiper motor in either of those? OK, you probably wouldn’t need to, but that’s beside the point. How about piling in a cubic yard of mulch or a half ton of firewood? Again, maybe so on all counts. My point isn’t to profess the superiority of a Land Rover over anything else (God knows, they’re deeply flawed), but for me, the combination of versatility, utility, and the intangible ways in which the DIY spirit bleeds into the rest of my life add up to a perfect match. I like to think that “versability” can apply equally to the owner, and not just the Land Rover.

Lovely sentiments, thank you for sharing. It’s musings like this that are at the heart of why I enjoy following your work (not that I don’t enjoy all of it). There’s a saying about how we’re the average of the five people we spend the most time with. I’m not sure it’s that simple, but I agree that we are influenced by the views and lifestyles of people around us, and we sometimes get a choice in those influences. I enjoy following your work because it’s one of those influences. Perhaps “influence” is a dirty word these days, and I merely mean that posts like this remind me that I do love working on stuff, that maybe I don’t need to hire out that job, and that camping really is how I want to spend my weekend. It’s a good influence!

Any thoughts on having a roll bar welded into the Series III? I’ve left the roof on my FJ40 and I have a bolted in (not welded) roll bar and it still scares me that’ll it’ll be a death trap if it rolls.