I’m no stranger to diving with rare, vintage watches. I’ve had two of my own antiques brought up to spec for a return to the briny deep: a Tudor Submariner and a Doxa SUB 200 T.Graph. I’m of the belief that it’s no different than if they’d been worn and used continuously—and serviced regularly—by their original owners, a practice even the most cautious collector would begrudgingly admire. But there was one vintage diver that did give me pause before back-rolling into very deep water. It was an early 1960s Tornek-Rayville TR-900. The watch belonged to Blancpain, the Swiss maker of high end timepieces. They assured me it was fully serviced and watertight and encouraged me to wear it as often as I wanted on dozens of dives in the waters around the Revillagigedos archipelago in the remote Eastern Pacific.

So why was I reluctant to dive with this one? Yes, it was expensive, worth about a year’s income for me. And yes it was rare, with only a few hundred ever made and only a handful that have survived. I think it’s because that watch has achieved such mythic status, beyond most other rare, expensive, iconic dive watches. It’s not like driving my own 1976 Land Rover, one of over 100,000 built, on snowy roads. It’s like being handed the keys to a 1948 Series I with registration HUE 166, the first production Land Rover, and being told to enjoy it. “Be sure to pump the brakes on the black ice, and just bring it back with a full tank before sundown!”

But, of course, I did take the old TR-900 diving and it did just fine, as good as any other dive watch I’ve worn, except for the slightly snug bezel, but for that I’m willing to cut it some slack. Honestly, once you’re underwater, a watch tends to fade into the background. A glance every now and then reminds you it’s tracking your bottom time, but then you don’t really notice it again until you’re back on the boat stripping off your kit. Then there’s the relief that A) it’s still fastened to your arm, and B) there’s no condensation under the crystal. Looking back, I actually remember the mantas, whale sharks, and schools of yellowfin tuna I saw more than I do the watch. Sorry to disappoint. That said, it remains a prominent notch on my diving weight belt to have had the privilege to take it deep.

Fast forward to the summer of 2020. I posted a photo of a T-shirt I was wearing on Instagram. On the back was stenciled “Tornek-Rayville U.S.” On my wrist was my own Blancpain Fifty Fathoms Bathyscaphe, an homage to the early Blancpains upon which the TR-900 was based. I received a message from someone affiliated with Blancpain, inquiring about the shirt. I told him I bought it from the newly re-launched Tornek-Rayville brand. He replied, “at least you’ve got the real watch on.”

The irony of that exchange was, I didn’t have the real watch on. The original Tornek-Rayville TR-900 was a tough little no-nonsense dive watch made for rough duty, built to military specification and on a military procurement budget. It had a simple, unadorned steel case, acrylic timing ring, and an off-the-shelf automatic caliber made by the now defunct movement maker, Anton Schild. My Bathyscaphe was a five-figure watch with beveled steel case, sapphire bezel, and housing an anti-magnetic, beautifully decorated movement built in-house by Blancpain that’s visible through the see-through caseback. It is an haute horlogerie tour de force, but it’s not a milspec dive watch, If the Navy procured these for its divers nowadays, you can bet there’d be a Congressional hearing about it.

Don’t get me wrong, I love my Blancpain. It nods to the very earliest dive watches, by the brand that arguably invented the genre, in an incredibly well made package. But it’s not really close to the original Tornek-Rayville, or even to a vintage Fifty Fathoms besides in appearance. It is an homage, in its appearance, and in its water resistance rating. So much of what draws me to those early dive watches is the way they encouraged use and inspired confidence while at the same time didn’t impose themselves in the equation of risk, safety, function, or adventure. They disappear when you need them to, but are also there when you need them to be. Rolex Subs used to do this. So did Seamasters and Doxas. Seikos still do. And so does the new Tornek-Rayville TR-660. This watch, both in appearance and, more importantly, in spirit, captures the essence of the original.

I’m not going to go into the specs or dimensions of the watch. You can find those elsewhere, on Tornek’s website, and in numerous reviews published when the watch first was released this past winter. Suffice it to say, it’s comfortable, accurate, legible, functional, and affordable. It’s no secret that the appeal of a wristwatch is largely aesthetic, first and foremost. And while I love my Seamaster for its swoopy, elegant case and laser engraved ceramic dial, sometimes you want something a bit more stark.

The TR-660 is stripped of any hint of adornment. The watch is all right angles and circles, its case entirely matte grey. The text on the dial serves merely for identification and basic facts. This is the horological equivalent of a palate cleanser, a saltine cracker in the midst of béarnaise sauces, confits, and glazes. Function has its own beauty. Things designed strictly for purpose are honest in their intention. Especially with watches nowadays, we’re so inundated with hyperbole, in design, features, and marketing that those that are absent of that stand out. Yes, there’s clearly a message around the TR-660: nostalgia. But it’s nostalgia for the way watches used to be used, not only the way they used to look.

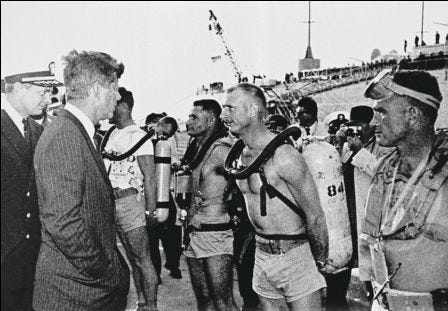

We talk a lot about tool watches and how you can do anything with them. Yet how many of us truly do that? Even a scuba dive isn’t really rough use. Sure, over years and hundreds of dives, on the wrist of a commercial or combat diver, or a dive instructor, straps break, bezels fall off, maybe the watch ultimately leaks. How about skiing, running, cutting the grass? Child’s play. Don’t read the Navy Experimental Diving Unit’s 1958 report (Project NS 186-200 Subtask 4, Test 43, 15 July, 1958) on its tests of a handful of dive watches if you get squeamish washing dishes wearing your Submariner. They dragged them on river bottoms, smothered them in mud, subjected them to extreme cold, heat, excessive depth, both in water and simulated, and, in general, tried to break them. Some did break, others didn’t. The Blancpain broke less than the others (for the record, they also tested an Enicar Sea Pearl and a Rolex Submariner) so they adopted it for use.

When I line up this new TR-660 Tornek-Rayville with my quiver of other dive watches, I can’t say it would break less than any of my others. But lying in my watch roll next to a Blancpain, a Rolex Sub, and a Seamaster, it sure seems to say, “go ahead and wear those others, but when you’re ready to get down to business I’ll be here waiting.” The sturdy, no-nonsense Seiko-derived movement inside (regulated to impressive accuracy, I might add), drilled lugs, and painted dial don’t say “luxury” like so many other watches do. That isn’t to say it feels or looks like a cheap thing. After all, it is still a $900 watch. On the contrary, it simply is one of those increasingly rare objects that simultaneously exudes equal auras of quality, utter functionality, and what I imagine will be longevity. It elicits the same feeling that I get upon finding a box of random woodworking tools in an antique store—planes, chisels, and clamps—that would slide back into service effortlessly and last another hundred years with only the occasional sharpening or oiling needed.

Though the Tornek-Rayville comes packaged with a fine rubber strap, the two provided ribbed nylon bands feel more fitting. One in a sort of British khaki and the other in black, they’re both like lengths of webbing cut and edges burned at a mountaineering shop, or adapted from an ammo pouch shoulder strap at the army surplus store. The watch transcends the sense of “looking the part” to actually inspire you to do something when wearing it. And not necessarily just diving. Tuck it in the top of your pack and strap it on before you lace up your boots to bag a peak or run some whitewater. Then treat it like you do the rest of your gear when you get home—hose it off, wipe it down, put it away. This could be your primary watch, but it also doesn’t seem to mind playing second fiddle to something more posh.

I am not averse to diving with my Blancpain Bathyscaphe, and I have. But when I do, it’s more out of a sense of smugness, a private moment of wearing something precious in a very unprecious setting. The Tornek-Rayville on the other hand elicits the exact opposite feeling, like when you’re lying in your tent during a rainstorm, smiling because you know the gear you packed is perfectly dialed in.

The elephant in the room, of course, with the Tornek-Rayville, is the name. It inspires debate surrounding so called “homage” watches, name appropriation, and zombie brands. A little background first: the original Tornek-Rayville, was made by the Swiss brand, Rayville S.A. (a phonetic anagram of the company’s home village, Villeret—“Rayville”), a company that also made Blancpains and some other department store watches. But there was a problem: the dive watch had to be “Americanized” to be procured for US military use. In order to get around a “buy American” government regulation, the New York-based watch importer, Allen V. Tornek, added his name to the watch and then, with some American parts and assembly to make it acceptable, it could be sold to the Pentagon.

So, in reality, the original Tornek-Rayville TR-900 was a watch assembled by Rayville S.A. with an off-the-shelf Schild movement, then branded Tornek-Rayville. Not so dissimilar to the new TR-660, that has a Seiko movement instead of a Schild, is assembled in Japan, regulated and QC’d in the US and then branded Tornek-Rayville. The original Tornek-Rayville name only lasted as long as that first run of watches bought for, and issued to, Navy divers in the early ‘60s. Yet the name has lived on in horological legend ever since. I think it’s perfectly fine to revive it in order to build a watch that carries forth the original spirit. If Blancpain (or some Tornek descendants) really wanted to do it, I assume they’d have done so by now anyway.

I haven’t dived with the TR-660 but I’m sure I will one day. I’m sure I’ll do a lot of things with this watch. Some will be dangerous, exotic, and adventuresome, but most will not be. There will also be gardening and hiking and car repair. And the watch will handle it all with no drama, gaining a few scratches perhaps, keeping time along the way, but probably simply fading into the background like a good honest tool watch should. Just like the original. Is the new TR-660 better than the old TR-900? I call it a draw. OK, maybe the new one is better, simply because you can actually buy one and won’t cost you a year’s salary.

"go ahead and wear those others, but when you’re ready to get down to business I’ll be here waiting." 👏👏👏

Good stuff! I can second the comment on Bills tuning of the movements, my MKII is easily the most accurate mechanical watch in the quiver, maybe even better than the quartz ones. If I hadn’t pulled the trigger on a SPB143 last year, this one would have been a no brainer. Currently waiting for the Paradives to restock, or maybe troll for an Adanac on the ‘bay…

Thanks for the continued good content!