It’s no great secret that my favorite kinds of watches are those made to go deep underwater. There’s something so defiant and mildly thrilling about taking a precision instrument into the ocean or a lake, fully exposed to the elements, where the weight of the water exerts almost 15 pounds per square inch of pressure every 30 feet you descend! At a time when rich guys can descend to the deepest points in the ocean in their luxe submersibles, and even an iPhone can survive the odd accidental dunking, it’s perhaps easy to take water resistance for granted. But cast your imagination back to the not so distant past, not even a century ago, when watches had no business being submerged, much less exposed to a downpour. Water is subversive, sneaky, and persistent. Anyone who’s been diving in a drysuit knows that even standing in waist deep water causes the suit to shrink-wrap itself to your thighs from the pressure. The tiniest of pinholes in a wrist or neck seal will leave you damp. And I’ve had several dive watches (even one rated to 1,000 meters) leak after less than an hour at recreational diving depths.

Given my respect for the properties of water pressure, you’d think I’d always want the most overbuilt, thick, triple-gasketed watch on my wrist—a Rolex Deepsea or Omega Ultra-Deep maybe. Nope. My tastes run even more niche. My favorite genre of watch is the dive chronograph, that aquatic Minotaur of the watch world—half diver, half stopwatch. In pursuit of even more usefulness, watchmakers stubbornly decided to take up the challenge and add two more holes to a watch case for push buttons. According to my casual research, Aquastar was the first brand to introduce a dive chronograph, in 1963—the Deepstar. This came only ten years after the first purpose-built dive watches arrived on the scene. What a sensation! The caseback proudly proclaimed “100% Waterproof” for anyone who had doubts about taking the plunge with one on his wrist. The Deepstar ushered in a golden era for the dive chrono. The following year, Breitling came out with its Superocean “slow motion” chronograph, and later came an embarrassment of riches, with everyone from Zodiac to Zenith to Bulova and Doxa bringing their underwater “time writers” to the deep.

I recall reading that dive chronographs were developed with the idea that a person could buy “two watches in one” — a dive watch that could also serve topside duty at the racetrack, in the kitchen, or in the lab, timing various things with the chrono functions. According to that theory, the pushers could be safely avoided around the water, but be called into duty back on dry land. But looking at some of the earliest examples, I tend to think they were made to serve as precision diving timers from the start. Of course, the pushers that are the calling card of any chronograph are also a dive watch’s Achilles heel. By definition, they’re made to be pushed and that can compromise the tiny rubber O-rings that stand between all those sneaky atmospheres of water pressure and the delicate cams, springs and gears inside the watch case. Nowadays it’s not uncommon to find locking pushers on dive watches that prevent operation, and, by extension, water ingress. But the earliest ones were simply friction fit, not meant to be pressed once submerged. But I’m sure people did it anyway.

Beyond the thumbed nose defiance of its arguably flawed form, what is it about the dive chronograph that appeals to me? For one thing, I’ve always loved the pure “instrument” look of a chronograph. The sweep hand stands at attention, vertical on the dial, like a needle and ready to be activated. The asymmetry of the push-pieces on one side of the case adds a visual interest, lending a very technical appearance. You recognize a chronograph across a room, whether it’s a Speedmaster or a Seamaster. Combine this with the broad shoulders and toothy timing ring of a dive watch and you’ve got a watch that means business.

Field watches and bog standard dive watches are simple creatures. Anyone can wear one and tell the time. With a dive chronograph, you have options. A chronograph wearer is someone who likes to interact with his watch, and needs to know how it works. Top button—start/stop, bottom button—reset. Read the elapsed time off on a couple of small registers. There’s a tactile pleasure you get engaging the mechanics of a chronograph movement—the slight resistance to the finger as you press the push-piece, the satisfying ‘click’ when it moves a cam or drives a column wheel. I’d contend that there are very few casual wearers of chronographs, and even less when it’s a dive chronograph.

I’m always interested in those who chose to wear chrono-divers back in the day when these were bought as proper tools to be used and not merely as collectible luxury curiosities—people like Apollo astronaut, Eugene Cernan, who owned a bright orange Doxa SUB 200 T.Graph. I like to think old Gene, being a former Navy pilot, liked instruments, liked the process of activating a stopwatch function, used it to time everything from drag racing his Corvette Stingray at Coco Beach to timing steaks on his backyard grill in Houston, to capsule water egress training in the Gulf. The watch would be worn loose on a beads-of-rice steel bracelet on his tanned arm, perhaps paired with a Ban-Lon polo shirt and harvest gold swim trunks. He’d reluctantly set it aside when it was time to suit up for a spaceflight simulations, slipping on the NASA issue Speedmaster, an equally iconic, but far more hydrophobic chronograph.

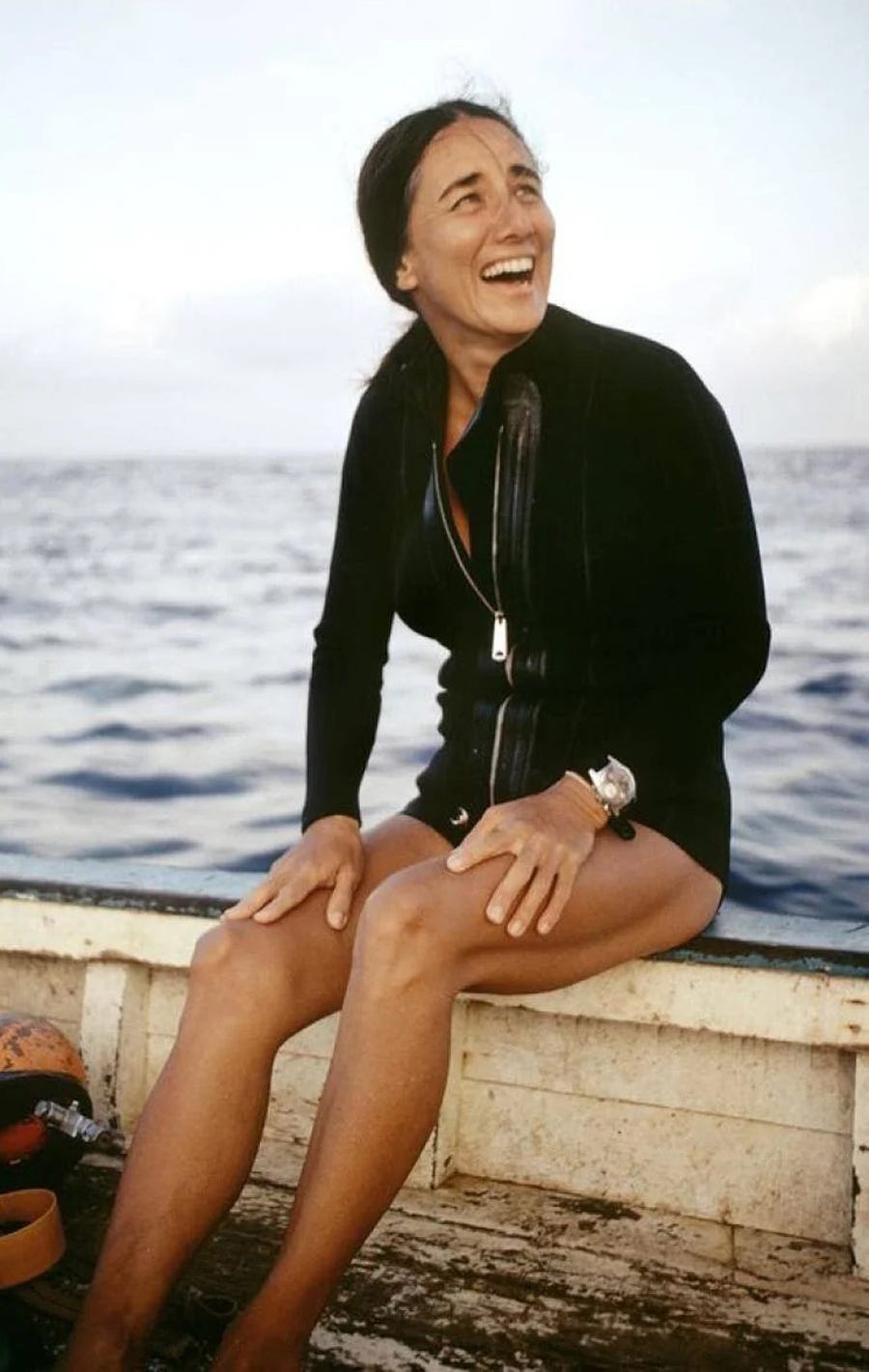

Or Eugenie Clark, the ichthyologist, who wore an Aquastar Deepstar for over a decade, perhaps using its oversized minute counter to make sure the sharks she was catching weren’t kept out of the water longer than three minutes while blood was drawn and a tag affixed to its dorsal fin. For her, I imagine, there was no romance to the watch; it was strapped on over a wetsuit sleeve, smacked on gunwales, and caked with dried salt from surface intervals in the Caribbean.

In my own collection, I have dive chronographs representing the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, as well as some contemporary ones. My oldest is a 1969 Doxa T.Graph Sharkhunter that was bought in a Chicago dive shop in 1970, then used for all manner of watersports, from sailing to waterskiing, to diving, for over a decade before it was retired. I bought it from its original owner, had it restored, and have returned it to the deep on more than one occasion. Next up is an Aquastar Benthos from the early ‘70s. It represents perhaps the high point of dive chronograph functionality, with its large central elapsed minute hand, chunky bezel, and 500 meters of water resistance. Due to a damaged inner gasket channel, it will enjoy a dry retirement, but I have no doubt it spent a good many hours underwater. There’s simply no way someone would have bought this watch to wear casually. From the ‘80s comes the Citizen Aqualand, an outlier to this catalog since it is a quartz analog-digital watch, but a chronograph nonetheless, albeit digital. I still think it qualifies. Then there’s a reissued Aquastar Deepstar, perhaps the prettiest of its breed, with full on midcentury styling and an arcane bezel scale I always forget how to use. A regatta timing Omega Seamaster, despite being marketed for racing skippers, still boasts 300 meters of water resistance and pushers that can be used underwater. I may be forgetting one or two.

The watches we choose to own and wear say a lot about us. A slim, elegant dress watch is all about refinement, sartorial sensibility, and urban panache. A pilot’s watch has swagger. A field watch is for those who want their timepiece to simply do its job, but get out of the way. A dive watch is pure adventure and derring-do. A chronograph—any chronograph—is to me the most interesting complication, pure function with a myriad of applications, and a true symbol of horological prowess. Combine these last two and you get something very special indeed, the watch nerd’s dive watch, bristling with potential energy and rugged capability. A dive chronograph demands to be used, challenges you to strap it on and go time new adventures—anywhere. Is it any wonder that I outfitted my novel’s hero with one? People often hope their watches can measure up and reflect their own lives. I hope I can live up to my watch. After all, its most important function is inspiration.

“And I’ve had several dive watches (even one rated to 1,000 meters) leak after less than an hour at recreational diving depths.” Yikes! 😳 Can you say which brand/model that was? Were you able to figure out a root cause for the failure, or was it just a 🤷🏻♂️?

Beautifully written Jason. I share your love of dive watches and dive chronographs. I just need to figure out how to get underwater more often!