I am nothing if not unpredictable. After declaring, both privately and publicly, that I’m done collecting vintage watches, in the past month I’ve come into possession of two more. To be fair, one of them was utter serendipity to the point of almost falling out of the sky. The other one was not quite the same story, but is a watch I’d previously owned that I really “needed” to have back on my wrist. I’ve been wearing both almost nonstop the past few weeks, and they’ve reminded me how much fun old, imperfect watches can be, and how expectations and conversations around modern watches tend to beat the joy right out of them sometimes. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The two watches I’ve acquired recently are from the same era, likely within two or three years of each other. But they couldn’t be more different. One is a Swiss chronograph that is funky, colorful, and dynamic—some might even call it ugly—and makes me smile and shake my head when I wear it. The other is a sober Japanese dive watch, muted and purpose-built. Both have clearly led interesting lives, or rather their original owners did, judging by their weathered appearances. I thought it would be fun to write about each of them, one this week, the other next week—how I got them, their imagined pasts, and why I love them. First, the Omega.

A couple weeks ago, a friend visited an estate sale in a Minneapolis neighborhood, where she saw a pile of old watches in various states of disrepair. She snapped a photo with her phone and sent it to Gishani, knowing that we liked watches. I pored over the photo, prepared to be, if not disappointed, at least not interested. Sure enough, most of the watches in the blurry snap were rather common pocketwatches, the kind seen at antique shops and garage sales all over the American Midwest—Elgins and Walthams mostly, maybe an odd Hamilton. But there, among them, was something completely different: a blue dial, massive steel case, on a bracelet. Could it be? I pinched and zoomed. Yes, it was—an Omega. I’d know it anywhere. There is nothing else like it, and about as unusual to find among a Minneapolis household’s bric-a-brac as a spaceship landing in a cornfield. In a moment of uncharacteristic spontaneity, we jumped in the car and drove to the address.

I’m not usually much for estate or garage sales, flea markets, or antique shops. I know there are treasures to be found at these places, but they require a lot of patience, and tolerance for dust, crowds, and tight quarters. And I’m really only interested in the watches, not old hand tools, lighters, faded postcards, and dated furniture. I did get lucky once before, finding a 1980s Seiko 7002 at an antique mall in southern Minnesota. I bought that one for $40. It is rough, as a Seiko dive watch should be, and has the previous owner’s initials hand engraved on one of the lugs. That was close to ten years ago. Maybe watch luck comes along once a decade.

I wound this one up, set the time, tested the chronograph function, and all worked. The woman running the sale said there were a couple of bids on it already, lower than the price written on the tag. I was surprised, and blurted out a number that I would pay for it. “Sold!” Then a scramble, on a Saturday afternoon, to run home to dig in the sofa cushions for the cash, then back to pay for it. The bracelet was even sized perfectly for my wrist. I walked out with it on. Clearly, it was fate, right?

The watch I now I own is an early 1970s Omega Speedmaster Mark III, ref. 176.002. It is undoubtedly of its era, with a preposterously oversized and avant-garde case that was probably the inspiration for Darth Vader’s helmet in the movie, Star Wars. It has a beautiful blue sunburst dial with a date window, and two registers, one for elapsed hours and one dual function one for a 24-hour indication and the running seconds. There are two overlayed sweep hands standing at attention at 12:00—a conventional white one for elapsed seconds, and an orange one with a prominent airplane shaped tip for tracking elapsed minutes.

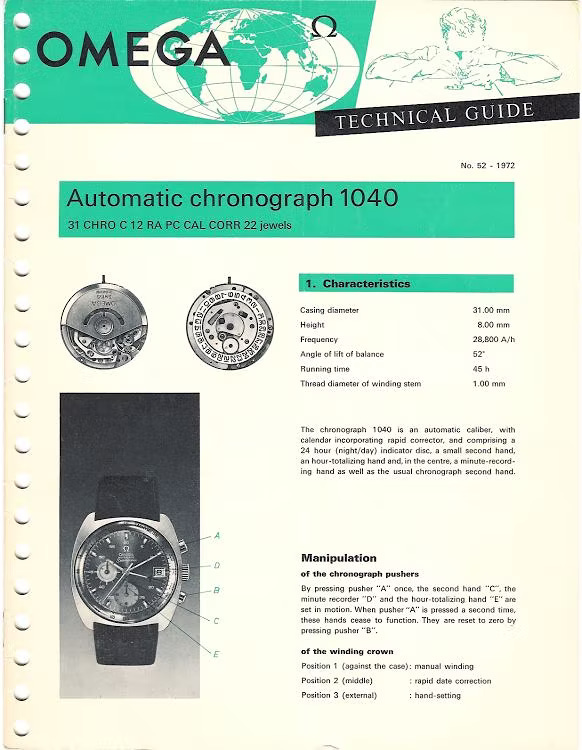

If the appearance of this watch isn’t spectacular enough, the functionality of it surely is. Center sweep minutes on a chronograph are exceedingly rare these days, but so much more legible. This Omega’s functions come courtesy of the movement inside, the caliber 1040, which is based on the Lemania 1341. This happened to be Omega’s very first self-winding chronograph, and the cal. 1040 was the predecessor of the much vaunted Lemania 5100 that appeared later.

I’ve had some history with this movement, and with blue-dialed Omegas that housed them. Way back in 2011, one of the first stories I wrote for Hodinkee was about a 1970s Seamaster diving chronograph, the fabled “Big Blue.”, Then I actually owned a different blue-dial Seamaster chronograph with the cal.1040. I clearly have a penchant for these things, which I also covered in print, er… pixels.

I also currently own a 1968 Speedmaster, the hand-wound legend that went to the Moon. That watch is a horological icon and a design masterpiece, with its classic lyre-shaped lugs, stark white-on-black dial, and domed acrylic crystal. This Mark III is no Moonwatch. By the ‘70s, Omega was taking chances with its designs, as evidenced by angular and bulbous watches like its 1000-meter diver, the oblong Dynamics, the mighty Ploprof, and the Flightmaster. This is the bell bottom jeans version of a Swiss watch, polarizing but unforgettable and utterly unique.

This Speedmaster Mark III was clearly loved by its former owner, as indicated by the state of its case and crystal. The sloping case, which would have originally had lovely radial brushed finishing, is covered in hairline scratches and legitimate dents. Similarly the mineral glass crystal is a web of scratches. There’s even a sizable crack across it and a small chunk of glass missing near the edge. I don’t know anything about the former owner, but was told he used to own a used car dealership for many years, and had accumulated dozens of cars of his own. In fact, as part of the estate sale, there was a 1974 Saab Sonett parked in the garage. It was tempting to make it a package deal. If you don’t know the Sonett (“so nice” in Swedish), do a Google search. It is the Speedmaster Mark III of cars.

Given the respective vintages of car and watch, it’s not hard to imagine this man driving his new green Saab, in his wide legged trousers and floral print polyester shirt (open to the navel, naturally), to a local jeweler in Minneapolis. It’s a nice summer day, one of the precious few that needs to be savored, and he has the window down. Credence Clearwater Revival is on the radio, and he’s singing along. He’s had a good month of sales at the car lot and he feels like celebrating with a new watch. At the retailer, he peruses the offerings in the display case. There are Rolexes in one case, sober and monochromatic. The Accutrons looks cool but he thinks the hum of the tuning fork movement would keep him awake. Seiko has some wild looking pieces, but he wants Swiss. Then he walks over to the Omega case.

There’s the Moonwatch, sitting like a holy relic from a bygone age. Then a few gold dress watches, a quartz Constellation with an integrated bracelet, and Omega’s own tuning fork watch, the f300. He considers a couple of Seamaster divers, but unless he falls off his aluminum fishing boat, he doesn’t need that kind of waterproofing. But there, at the end, sits this Speedmaster Mark III, impossibly huge, its flanks reflecting the hot display lights. The blue dial stands out among all the black and silver and white watches surrounding it. The salesperson takes it out and lets him play with the chronograph. He tries it on. It’s big and heavy for sure, but he’s a big guy. He can pull off the look. “I’ll take it,” he says.

“Cash, check, or layaway?”

“I’ll pay cash.”

Wound, set, on the wrist, out the door, and into the Saab, to be worn nonstop for the next 30 years. He must have done everything wearing this watch, judging by its current state: changing the Saab’s oil, putting up storm windows for winter, fishing for walleye at his cabin, mowing the grass… Trust me, it’s not the kind of watch that lends itself to that sort of daily wear. It’s HUGE, sitting a full 16 millimeters off the wrist, top heavy on its rattly bracelet, prone to bashing on door frames.

Now, in reality, I don’t know how this Omega Speedmaster Mark III was worn, or the story behind it, but I’m choosing to believe my imaginary version of it. I guess that’s the beauty of vintage watches. Because they’re not imbued with our own stories, we can make ones up, then add to them. The watch needs a service, and a new crystal. It keeps pretty good time, but the chronograph sweep seconds stops randomly now and then, even though the minute counter keeps going. I’ll send it off for an overhaul someday. But I’m in no hurry. I love looking at all the scratches and dings up close. How often, when we buy a new watch, do we cringe at that first scratch? How often do any of us even manage to put a half dozen blemishes on our prized watches before we get them polished and serviced? Is that love? If you could see this Omega up close, you’d see that this guy loved his watch. And I don’t want erase any of that. I’m going to wear it for a while like this.

Next week, I’ll tell you about the Seiko I got. But now, if you’ll excuse me, the needle is skipping. It’s time to go flip the record over.

My Father owns the same 176.006 you used to have. He bought it new from the military PX when he was in the Air Force in ‘73. He’s basically worn it everyday since he bought it, with the exception of the two times it’s been overhauled. It’s amazing how much character it has.

Funny Jason that you purchased this Omega. Just a coincidence but I happened upon a Tag Heuer Aquagraph 500 meter Diving Chronograph last week. It's about 20 years old, large, chunky, and has the Central minute counter using an ETA movement with a Dubois Depraz module. Such a cool and funky watch. Bought for less than a grand. I love it!